RTI Connext

Core Libraries and Utilities

User’s Manual

Version 5.0

RTI Connext

Core Libraries and Utilities

User’s Manual

Version 5.0

© 2012

All rights reserved.

Printed in U.S.A. First printing.

August 2012.

Trademarks

Copy and Use Restrictions

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form (including electronic, mechanical, photocopy, and facsimile) without the prior written permission of Real- Time Innovations, Inc. The software described in this document is furnished under and subject to the RTI software license agreement. The software may be used or copied only under the terms of the license agreement.

Note: In this section, "the Software" refers to

This product implements the DCPS layer of the Data Distribution Service (DDS) specification version 1.2 and the DDS Interoperability Wire Protocol specification version 2.1, both of which are owned by the Object Management, Inc. Copyright

Portions of this product were developed using ANTLR (www.ANTLR.org). This product includes software developed by the University of California, Berkeley and its contributors.

Portions of this product were developed using AspectJ, which is distributed per the CPL license. AspectJ source code may be obtained from Eclipse. This product includes software developed by the University of California, Berkeley and its contributors.

Portions of this product were developed using MD5 from Aladdin Enterprises.

Portions of this product include software derived from Fnmatch, (c) 1989, 1993, 1994 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. The Regents and contributors provide this software "as is" without warranty.

Portions of this product were developed using EXPAT from Thai Open Source Software Center Ltd and Clark Cooper Copyright (c) 1998, 1999, 2000 Thai Open Source Software Center Ltd and Clark Cooper Copyright (c) 2001, 2002 Expat maintainers. Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions: The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

Technical Support

232 E. Java Drive

Sunnyvale, CA 94089

Phone: |

(408) |

Email: |

support@rti.com |

Website: |

Available Documentation

To get you up and running as quickly as possible, we have divided the RTI® Connext™ (for- merly, RTI Data Distribution Service) documentation into several parts.

❏Getting Started Guide

If you want to use the Connext Extensible Types feature, please read:

• Addendum for Extensible Types (RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities_GettingStarted _ExtensibleTypesAddendum.pdf) Extensible Types allow you to define data types in a more flexible way. Your data types can evolve over

If you are using Connext on an embedded platform or with a database, you will find additional documents that specifically address these configurations:

•Addendum for Embedded Systems (RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities_GettingStarted _EmbeddedSystemsAddendum.pdf)

•Addendum for Database Setup (RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities_GettingStarted

_DatabaseAddendum.pdf).

❏What’s New

❏Release Notes and Platform Notes (RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities_ReleaseNotes.pdf and

❏Core Libraries and Utilities User’s Manual (RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities

❏API Reference Documentation (ReadMe.html, RTI_CoreLibrariesAndUtilities

iii

The Programming How To's provide a good place to begin learning the APIs. These are hyperlinked code snippets to the full API documentation. From the ReadMe.html file, select one of the supported programming languages, then scroll down to the Program- ming How To’s. Start by reviewing the Publication Example and Subscription Example, which provide

Many readers will also want to look at additional documentation available online. In particular, RTI recommends the following:

❏The RTI Customer Portal, https://support.rti.com, provides access to RTI software, doc- umentation, and support. It also allows you to log support cases. Furthermore, the portal provides detailed solutions and a free public knowledge base. To access the software, documentation or log support cases, the RTI Customer Portal requires a username and password. You will receive this in the email confirming your purchase. If you do not have this email, please contact license@rti.com. Resetting your login password can be done directly at the RTI Customer Portal.

❏

•Example Performance Test (available for C++, Java

❏Whitepapers and other

1. RTI Connext .NET language binding is currently supported for C# and C++/CLI.

iv

Contents

|

|

Available Documentation.............................................................. |

iii |

|

|

|

Welcome to RTI Connext............................................................................ |

xix |

|

|

|

xix |

||

|

|

|

xix |

|

|

|

|

xix |

|

|

|

|

xix |

|

|

|

xx |

||

|

||||

Overview............................................................................................ |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

2.1.1 DCPS for |

||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

3 Data Types and Data Samples ........................................................ |

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

Registering |

||

v

................................................................................................ |

||

Enabling Entities ....................................................................................................................... |

||

Getting the StatusCondition |

||

4.2.1 .......................................QoS Requested vs. Offered |

||

vi

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

4.3.2 Special |

||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

4.4.2 Creating and Deleting Listeners........................................................................................... |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

4.6.1 Creating and Deleting WaitSets............................................................................................ |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

4.6.4 Processing Triggered |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

5.4.2 Where Filtering is |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

Sending Data..................................................................................... |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

vii

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Using a |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Managing Data Instances (Working with Keyed Data Types)......................................... |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

ASYNCHRONOUS_PUBLISHER QosPolicy (DDS Extension) ...................................... |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

DATA_WRITER_PROTOCOL QosPolicy (DDS Extension)............................................. |

||

|

DATA_WRITER_RESOURCE_LIMITS QosPolicy (DDS Extension).............................. |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

MULTI_CHANNEL QosPolicy (DDS Extension)............................................................ |

||

|

|||

viii

TRANSPORT_SELECTION QosPolicy (DDS Extension)............................................... |

||

TRANSPORT_UNICAST QosPolicy (DDS Extension) ................................................... |

||

Managing Fast DataWriters When Using a FlowController .......................................... |

||

Creating and Configuring Custom FlowControllers with Property QoS .................... |

||

Receiving Data.................................................................................. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

7.2.5 Beginning and Ending |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

7.4.1 Using a |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

ix

8 Working with Domains ...................................................................... |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Choosing a Domain ID and Creating Multiple Domains................................................. |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

SYSTEM_RESOURCE_LIMITS QoS Policy (DDS Extension).......................................... |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

DISCOVERY_CONFIG QosPolicy (DDS Extension)......................................................... |

||

|

DOMAIN_PARTICIPANT_RESOURCE_LIMITS QosPolicy (DDS Extension) ............ |

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

TRANSPORT_BUILTIN QosPolicy (DDS Extension) ....................................................... |

||

|

TRANSPORT_MULTICAST_MAPPING QosPolicy (DDS Extension)........................... |

||

|

|||

x

|

|||

|

|||

11 Collaborative DataWriters.............................................................. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

11.3.3 Specifying which DataWriters will Deliver Samples to the DataReader from a Logical |

|

|

Data |

|

|

||

xi

xii

xiii

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

xiv

21 Troubleshooting............................................................................... |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Part 4:

xv

Getting Requests and Sending Replies with a SimpleReplierListener ......................... |

||

Part 5: RTI Secure WAN Transport

25 Configuring RTI Secure WAN Transport ......................................... |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

Part 6: RTI Persistence Service

Introduction to RTI Persistence Service......................................... |

||||

Configuring Persistence Service.................................................... |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

xvi

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

Sample Memory Management With Durable Subscriptions ......................................... |

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

Running RTI Persistence Service .................................................... |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Administering Persistence Service from a Remote Location...... |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||

Advanced Persistence Service Scenarios ................................... |

||||

|

Scenario: |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

Part 7: RTI CORBA Compatibility Kit

Introduction to RTI CORBA Compatibility Kit ................................ |

|||

Generating |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

xvii

33 Supported IDL Types ....................................................................... |

Part 8: RTI RTSJ Extension Kit

Introduction to RTI RTSJ Extension Kit............................................. |

||

Using RTI RTSJ Extension Kit ............................................................ |

36 Configuring the RTI TCP Transport.................................................. |

|

xviii

Welcome to RTI Connext

RTI Connext solutions provide a flexible data distribution infrastructure for integrating data sources of all types. At its core is the world's leading

Conventions

The terminology and example code in this manual assume you are using C++ without namespace support.

C, C++/CLI, C#, and Java APIs are also available; they are fully described in the API Reference HTML documentation.

Namespace support in C++, C++/CLI, and C# is also available; see the API Reference HTML documentation (from the Modules page, select Using DDS:: Namespace) for details.

Extensions to the DDS Standard

Connext implements the DDS Standard published by the OMG. It also includes features that are extensions to DDS. These include additional Quality of Service parameters, function calls, struc- ture fields, etc.

Extensions also include

Environment Variables

Connext documentation refers to pathnames that have been customized during installation. NDDSHOME refers to the installation directory of Connext.

Names of Supported Platforms

Connext runs on several different target platforms. To support this vast array of platforms, Con- next separates the executable, library, and object files for each platform into individual directo- ries.

xix

Each platform name has four parts: hardware architecture, operating system, operating system version and compiler. For example, i86Linux2.4gcc3.2 is the directory that contains files specific to Linux® version 2.4 for the Intel processor, compiled with gcc version 3.2.

For a full list of supported platforms, see the Platform Notes.

Additional Resources

The details of each API (such as function parameters, return values, etc.) and examples are in the API Reference HTML documentation. In case of discrepancies between the information in this document and the API Reference HTML documentation, the latter should be considered more

xx

Part 1: Introduction

This introduces the general concepts behind

1

Chapter 1 Overview

RTI Connext (formerly, RTI Data Distribution Service) is network middleware for distributed real- time applications. Connext simplifies application development, deployment and maintenance and provides fast, predictable distribution of

With Connext, you can:

❏Perform complex

❏Customize application operation to meet various

❏Provide

❏Use a variety of transports.

This chapter introduces basic concepts of middleware and common communication models, and describes how Connext’s

1.1What is Connext?

Connext is network middleware for

Connext implements the

With Connext, systems designers and programmers start with a

What is Middleware?

1.2What is Middleware?

Middleware is a software layer between an application and the operating system. Network middle- ware isolates the application from the details of the underlying computer architecture, operating system and network stack (see Figure 1.1). Network middleware simplifies the development of distributed systems by allowing applications to send and receive information without having to program using

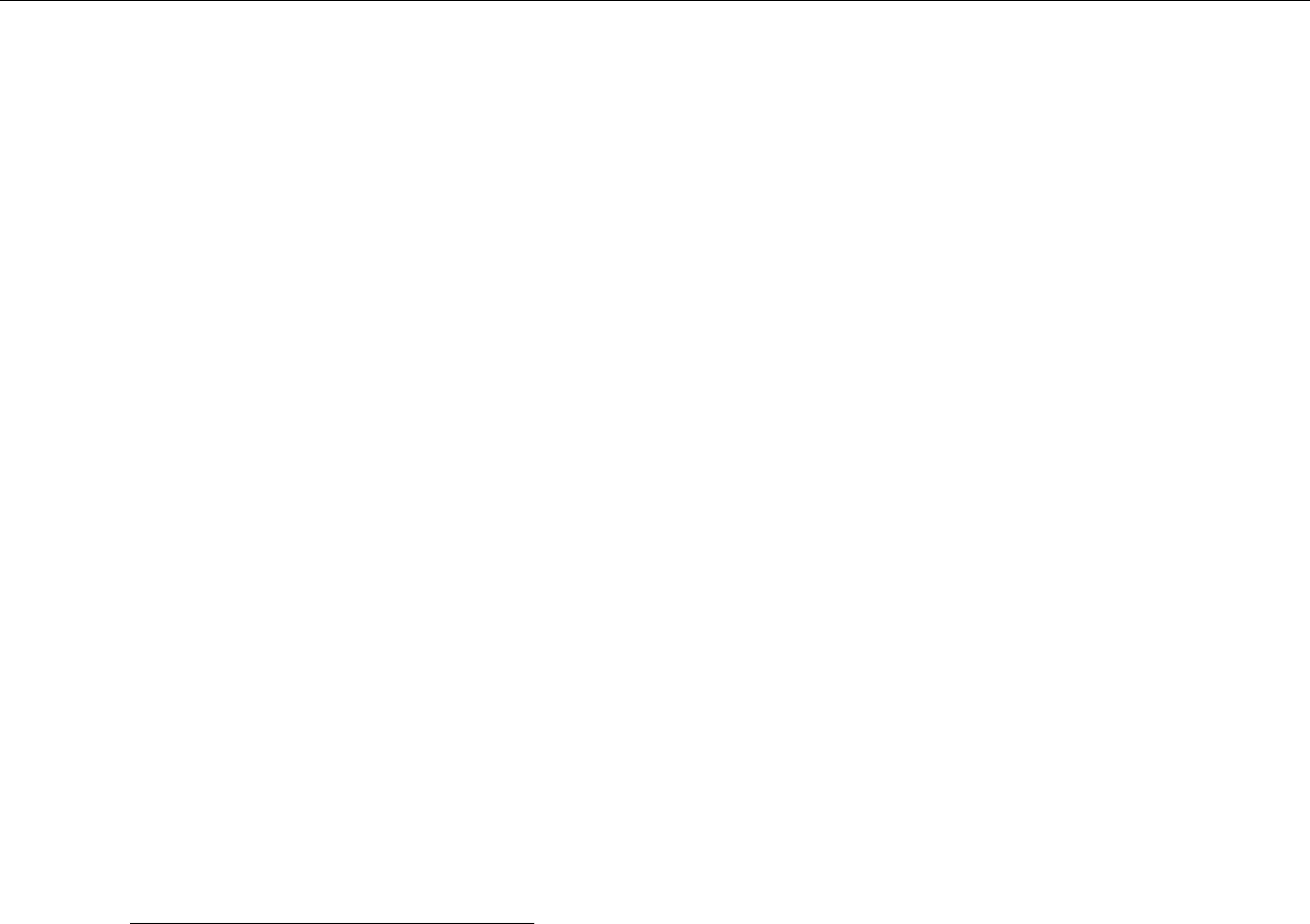

Figure 1.1 Network Middleware

Connext is middleware that insulates applications from the raw

Despite the simplicity of the model, PS middleware can handle complex patterns of information flow. The use of PS middleware results in simpler, more modular distributed applications. Per- haps most importantly, PS middleware can automatically handle all network chores, including connections, failures, and network changes, eliminating the need for user applications to pro- gram of all those special cases. What experienced network middleware developers know is that handling special cases accounts for over 80% of the effort and code.

1.3Network Communications Models

The communications model underlying the network middleware is the most important factor in how applications communicate. The communications model impacts the performance, the ease to accomplish different communication transactions, the nature of detecting errors, and the robustness to different error conditions. Unfortunately, there is no “one size fits all” approach to distributed applications. Different communications models are better suited to handle different classes of application domains.

This section describes three main types of network communications models:

❏

❏

Network Communications Models

❏

TCP is a

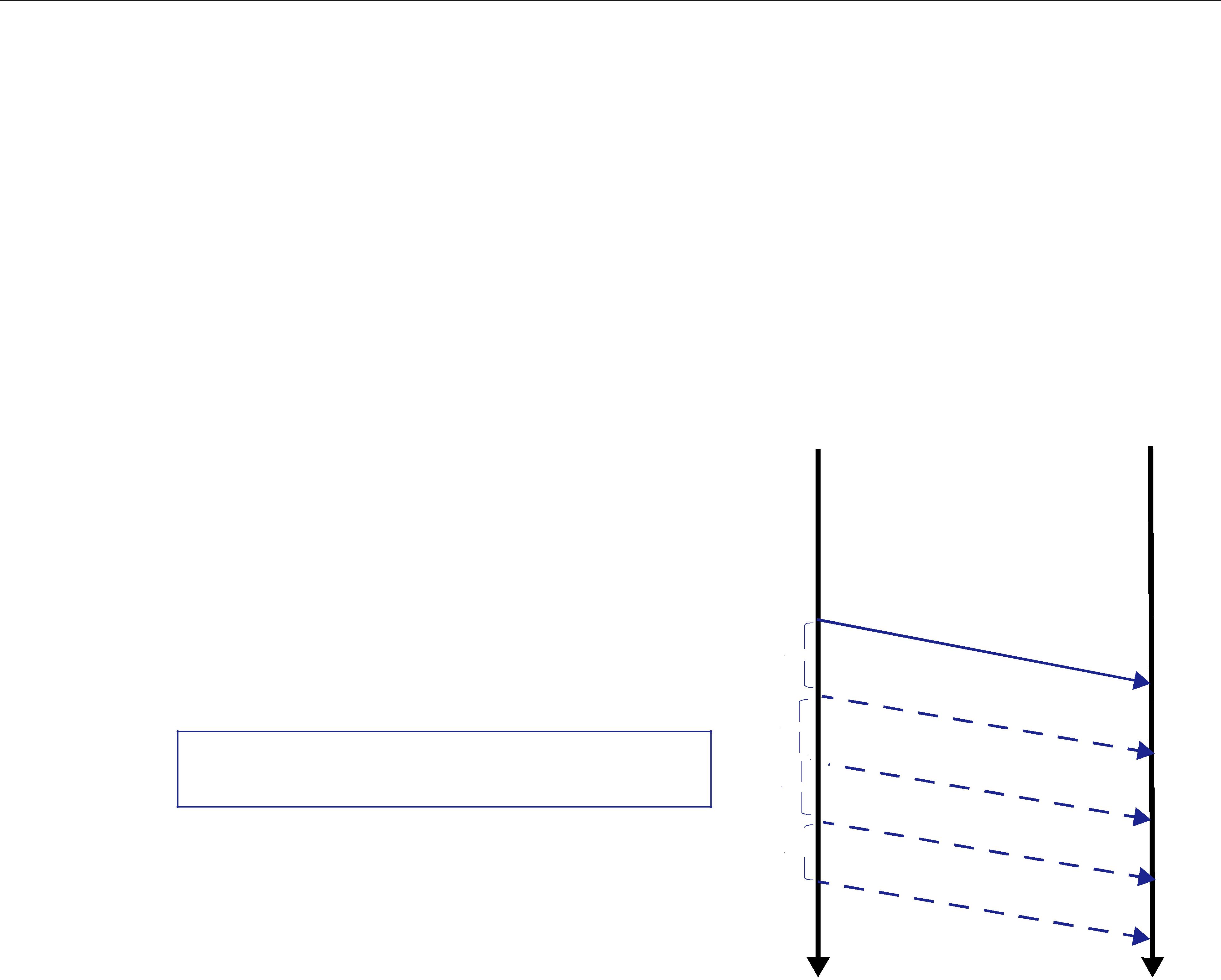

Figure 1.2

A

B

The

Figure 1.3

Client |

Client |

|

Server |

request |

Client |

Client |

reply |

|

Features of Connext

While the

❏

❏Remote Method Invocation (alternate solutions: CORBA, COM, SOAP)

❏

❏Synchronous transfers (alternate solution: CORBA)

Figure 1.4

Subscriber |

Subscriber |

|

Publisher |

Subscriber

Publisher

1.4Features of Connext

Connext supports mechanisms that go beyond the basic

❏determining who should receive the messages,

❏where recipients are located,

❏what happens if messages cannot be delivered.

This is made possible by how Connext allows the user to specify Quality of Service (QoS) param- eters as a way to configure

Furthermore, Connext includes the following features, which are designed to meet the needs of distributed

❏

• Clear semantics for managing multiple sources of the same data.

Features of Connext

•Efficient data transfer, customizable Quality of Service, and error notification.

•Guaranteed periodic samples, with maximum rate set by subscriptions.

•Notification by a callback routine on data arrival to minimize latency.

•Notification when data does not arrive by an expected deadline.

•Ability to send the same message to multiple computers efficiently.

❏

❏Reliable messaging Enables subscribing applications to specify reliable delivery of samples.

❏Multiple Communication Networks Multiple independent communication networks (domains) each using Connext can be used over the same physical network. Applications are only able to participate in the domains to which they belong. Individual applications can be configured to participate in multiple domains.

❏Symmetric architecture Makes your application robust:

•No central server or privileged nodes, so the system is robust to node failures.

•Subscriptions and publications can be dynamically added and removed from the sys- tem at any time.

❏Pluggable Transports Framework Includes the ability to define new transport

❏Multiple

❏

❏

❏Compliance with Standards

•API complies with the DCPS layer of the OMG’s DDS specification.

•Data types comply with OMG Interface Definition Language™ (IDL).

•Data packet format complies with the International Engineering Consortium’s (IEC’s) publicly available specification for the RTPS wire protocol.

Chapter 2

Communications

This chapter describes the formal communications model used by Connext: the

This chapter includes the following sections:

❏Data Types, Topics, Keys, Instances, and Samples (Section 2.2)

❏DataWriters/Publishers and DataReaders/Subscribers (Section 2.3)

❏Domains and DomainParticipants (Section 2.4)

❏Quality of Service (QoS) (Section 2.5)

❏Application Discovery (Section 2.6)

2.1What is DCPS?

DCPS is the portion of the OMG DDS (Data Distribution Service) Standard that addresses data- centric

The

The

In contrast, in

What is DCPS?

types of method arguments). An

Data and

2.1.1DCPS for

DCPS, and specifically the Connext implementation, is well suited for

Efficiency

Determinism

Flexible delivery bandwidth Typical

DCPS allows subscribers to the same data to set individual limits on how fast data should be delivered each subscriber. This is similar to how some people get a newspaper every day while others can subscribe to only the Sunday paper.

Thread awareness

Connext provides

Data Types, Topics, Keys, Instances, and Samples

DCPS, and thus Connext, was designed and implemented specifically to address the require- ments above through configuration parameters known as QosPolicies defined by the DCPS standard (see QosPolicies (Section 4.2)). The following section introduces basic DCPS terminol- ogy and concepts.

2.2Data Types, Topics, Keys, Instances, and Samples

In

Within different programming languages there are several ‘primitive’ data types that all users of that language naturally share (integers, floating point numbers, characters, booleans, etc.). How- ever, in any

struct Time { long year; short day; short hour; short minute; short second;

};

struct StockPrice { float price; Time timeStamp;

};

Within a set of applications using DCPS, the different applications do not automatically know the structure of the data being sent, nor do they necessarily interpret it in the same way (if, for instance, they use different operating systems, were written with different languages, or were compiled with different compilers). There must be a way to share not only the data, but also information about how the data is structured.

In DCPS, data definitions are shared among applications using OMG IDL, a

2.2.1Data Topics — What is the Data Called?

Shared knowledge of the data types is a requirement for different applications to communicate with DCPS. The applications must also share a way to identify which data is to be shared. Data (of any data type) is uniquely distinguished by using a name called a Topic. By definition, a Topic corresponds to a single data type. However, several Topics may refer to the same data type.

Topics interconnect DataWriters and DataReaders. A DataWriter is an object in an application that tells Connext (and indirectly, other applications) that it has some values of a certain Topic. A cor- responding DataReader is an object in an application that tells Connext that it wants to receive values for the same Topic. And the data that is passed from the DataWriter to the DataReader is of the data type associated with the Topic. DataWriters and DataReaders are described more in Section 2.3.

Data Types, Topics, Keys, Instances, and Samples

For a concrete example, consider a system that distributes stock quotes between applications. The applications could use a data type called StockPrice. There could be multiple Topics of the StockPrice data type, one for each company’s stock, such as IBM, MSFT, GE, etc. Each Topic uses the same data type.

Data Type: StockPrice

struct StockPrice { float price;

Time timeStamp;

};

Topic: “IBM”

Topic: “MSFT”

Topic: “GE”

Now, an application that keeps track of the current value of a client’s portfolio would subscribe to all of the topics of the stocks owned by the client. As the value of each stock changes, the new price for the corresponding topic is published and sent to the application.

2.2.2Samples, Instances, and Keys

The value of data associated with a Topic can change over time. The different values of the Topic passed between applications are called samples. In our

For a data type, you can select one or more fields within the data type to form a key. A key is something that can be used to uniquely identify one instance of a Topic from another instance of the same Topic. Think of a key as a way to

However, for topics with keys, a unique value for the key identifies a unique instance of the topic. Samples are then updates to particular instances of a topic. Applications can subscribe to a topic and receive samples for many different instances. Applications can publish samples of one, all, or any number of instances of a topic. Many quality of service parameters actually apply on a per instance basis. Keys are also useful for subscribing to a group of related data streams (instances) without

For example, let’s change the StockPrice data type to include the symbol of the stock. Then instead of having a Topic for every stock, which would result in hundreds or thousands of topics and related DataWriters and DataReaders, each application would only have to publish or sub- scribe to a single Topic, say “StockPrices.” Successive values of a stock would be presented as successive samples of an instance of “StockPrices”, with each instance corresponding to a single stock symbol.

Data Type: StockPrice

struct StockPrice { float price; Time timeStamp;

char *symbol; //@key

};

Instance 1 = (Topic: “StockPrices”) + (Key: “MSFT”)

sample a, price = $28.00

sample b, price = $27.88

DataWriters/Publishers and DataReaders/Subscribers

Instance 2 = (Topic: “StockPrices”) + (Key: “IBM”)

sample a, price = $74.02

sample b, price = $73.50

Etc.

Just by subscribing to “StockPrices,” an application can get values for all of the stocks through a single topic. In addition, the application does not have to subscribe explicitly to any particular stock, so that if a new stock is added, the application will immediately start receiving values for that stock as well.

To summarize, the unique values of data being passed using DCPS are called samples. A sample is a combination of a Topic (distinguished by a Topic name), an instance (distinguished by a key), and the actual user data of a certain data type. As seen in Figure 2.1 on page

Figure 2.1 Relationship of Topics, Keys, and Instances

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a_type:instance1 |

Type:a_type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key = key1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key = ... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Topic:a_topic |

|

|

|

a_type:instance2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key = key2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a_type:instance3

Key = key3

By using keys, a Topic can identify a collection of

2.3DataWriters/Publishers and DataReaders/Subscribers

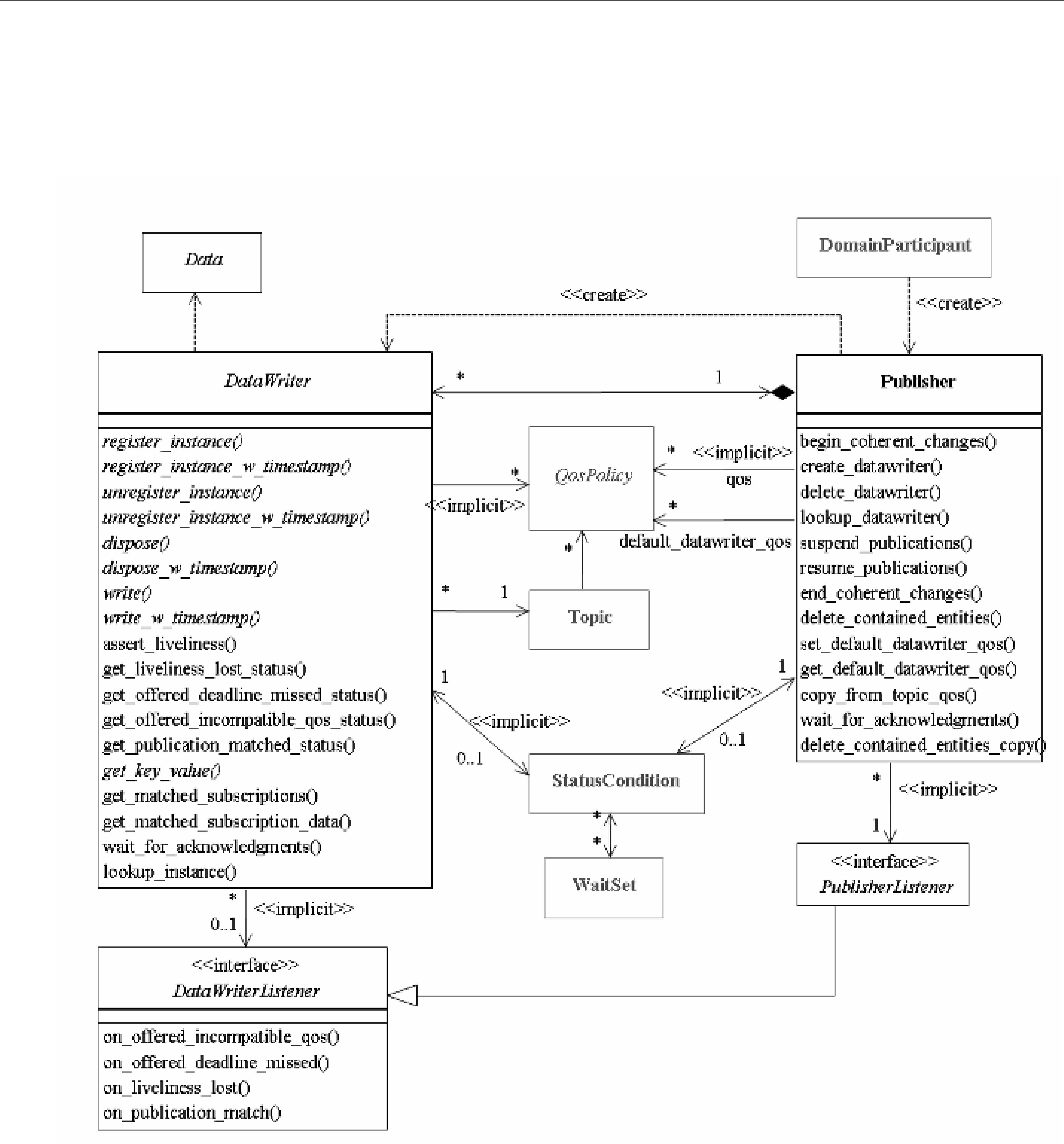

In DCPS, applications must use APIs to create entities (objects) in order to establish

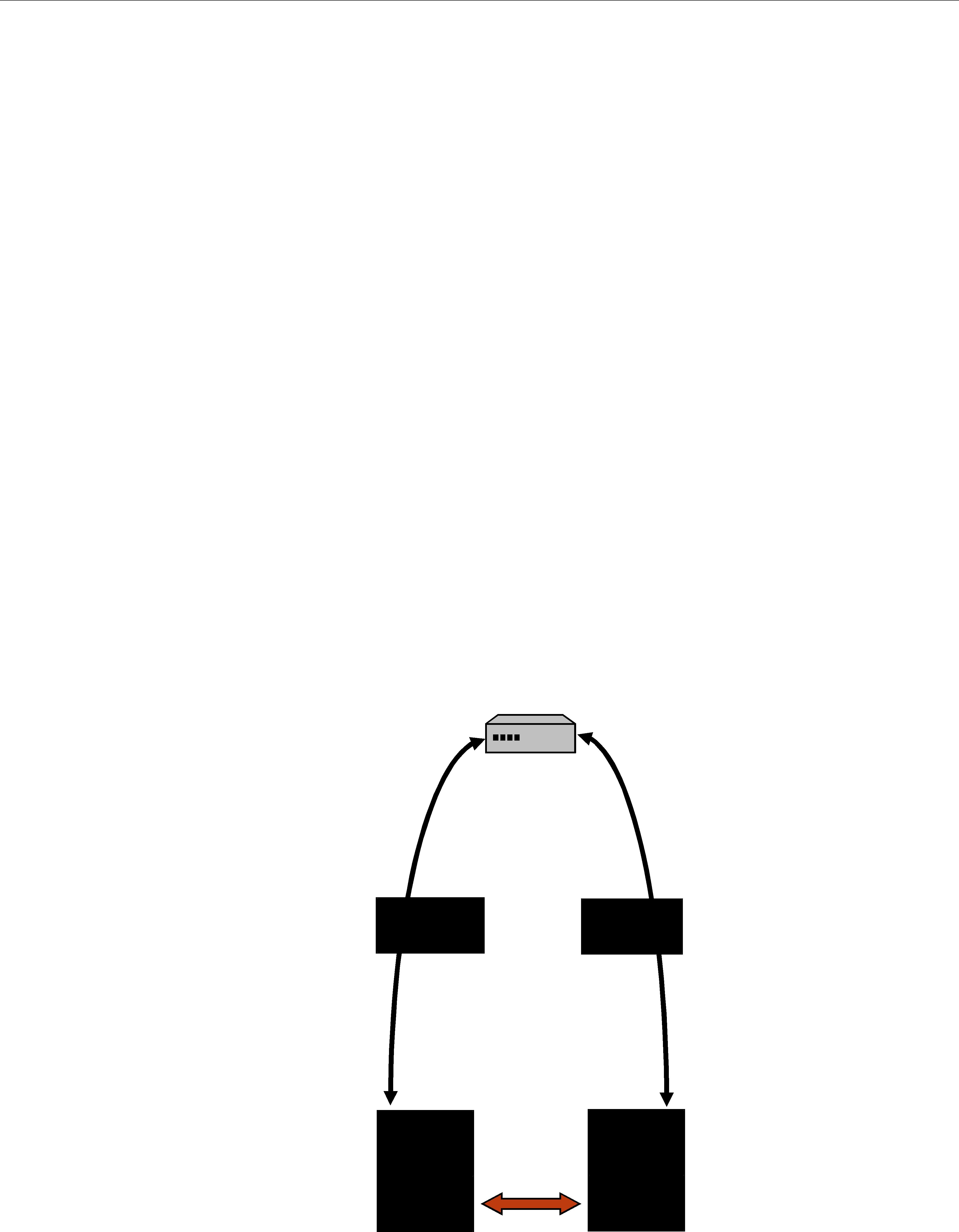

The sending side uses objects called Publishers and DataWriters. The receiving side uses objects called Subscribers and DataReaders. Figure 2.2 illustrates the relationship of these objects.

❏An application uses DataWriters to send data. A DataWriter is associated with a single Topic. You can have multiple DataWriters and Topics in a single application. In addition, you can have more than one DataWriter for a particular Topic in a single application.

DataWriters/Publishers and DataReaders/Subscribers

Figure 2.2 Overview

❏A Publisher is the DCPS object responsible for the actual sending of data. Publishers own and manage DataWriters. A DataWriter can only be owned by a single Publisher while a Publisher can own many DataWriters. Thus the same Publisher may be sending data for many different Topics of different data types. When user code calls the write() method on a DataWriter, the data sample is passed to the Publisher object which does the actual dis- semination of data on the network. For more information, see Chapter 6: Sending Data.

❏The association between a DataWriter and a Publisher is often referred to as a publication although you never create a DCPS object known as a publication.

❏An application uses DataReaders to access data received over DCPS. A DataReader is asso- ciated with a single Topic. You can have multiple DataReaders and Topics in a single appli- cation. In addition, you can have more than one DataReader for a particular Topic in a single application.

❏A Subscriber is the DCPS object responsible for the actual receipt of published data. Sub- scribers own and manage DataReaders. A DataReader can only be owned by a single Sub- scriber while a Subscriber can own many DataReaders. Thus the same Subscriber may receive data for many different Topics of different data types. When data is sent to an application, it is first processed by a Subscriber; the data sample is then stored in the appropriate DataReader. User code can either register a listener to be called when new data arrives or actively poll the DataReader for new data using its read() and take() meth- ods. For more information, see Chapter 7: Receiving Data.

❏The association between a DataReader and a Subscriber is often referred to as a subscription although you never create a DCPS object known as a subscription.

Example: The

Domains and DomainParticipants

mat of the information, e.g., a printed magazine. The user data is the contents (text and graphics) of each sample (weekly issue). The middleware is the distribution service (usually the US Postal service) that delivers the magazine from where it is created (a printing house) to the individual subscribers (people’s homes). This analogy is illustrated in Figure 2.3. Note that by subscribing to a publication, subscribers are requesting current and future samples of that publication (such as once a week in the case of Newsweek), so that as new samples are published, they are delivered without having to submit another request for data.

Figure 2.3 An Example of

Topic = "Newsweek" |

|

|

|

Topic = "Newsweek" |

||

|

|

Sample |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher |

Issue for Feb. 15 |

Subscriber |

||||

|

Send |

|

|

|

Receive |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Delivery |

|

Service |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

The

By default, each data sample is propagated individually, independently, and uncorrelated with other samples. However, an application may request that several samples be sent as a coherent set, so that they may be interpreted as such on the receiving side.

2.4Domains and DomainParticipants

You may have several independent DCPS applications all running on the same set of computers. You may want to isolate one (or more) of those applications so that it isn’t affected by the others. To address this issue, DCPS has a concept called Domains.

Domains represent logical, isolated, communication networks. Multiple applications running on the same set of hosts on different Domains are completely isolated from each other (even if they are on the same machine). DataWriters and DataReaders belonging to different domains will never exchange data.

Applications that want to exchange data using DCPS must belong to the same Domain. To belong to a Domain, DCPS APIs are used to configure and create a DomainParticipant with a spe- cific Domain Index. Domains are differentiated by the Domain Index (an integer value). Applica- tions that have created DomainParticipants with the same Domain Index belong to the same

Domain. DomainParticipants own Topics, Publishers and Subscribers which in turn owns DataWrit- ers and DataReaders. Thus all DCPS Entities belong to a specific domain.

An application may belong to multiple domains simultaneously by creating multiple Domain- Participants with different domain indices. However, Publishers/DataWriters and Subscribers/

DataReaders only belong to the domain in which they were created.

As mentioned before, multiple domains may be used for application isolation which is useful when users are testing their applications using computers on the same network or even the same computers. By assigning each user different domains, one can guarantee that the data pro- duced by one user’s application won’t accidentally be received by another. In addition, domains

Quality of Service (QoS)

may be a way to scale and construct larger systems that are composed of

For more information, see Chapter 8: Working with Domains.

2.5Quality of Service (QoS)

The

2.5.1Controlling Behavior with Quality of Service (QoS) Policies

QosPolicies control many aspects of how and when data is distributed between applications. The overall QoS of the DCPS system is made up of the individual QosPolicies for each DCPS

Entity. There are QosPolicies for Topics, DataWriters, Publishers, DataReaders, Subscribers, and DomainParticipants.

On the publishing side, the QoS of each Topic, the Topic’s DataWriter, and the DataWriter’s Pub- lisher all play a part in controlling how and when data samples are sent to the middleware. Sim- ilarly, the QoS of the Topic, the Topic’s DataReader, and the DataReader’s Subscriber control behavior on the subscribing side.

Users will employ QosPolicies to control a variety of behaviors. For example, the DEADLINE policy sets up expectations of how often a DataReader expects to see samples. The OWNERSHIP and OWNERSHIP_STRENGTH policy are used together to configure and arbitrate whose data is passed to the DataReader when there are multiple DataWriters for the same instance of a Topic. The HISTORY policy specifies whether a DataWriter should save old data to send to new sub- scriptions that join the network later. Many other policies exist and they are presented in QosPolicies (Section 4.2).

Some QosPolicies represent “contracts” between publications and subscriptions. For communi- cations to take place properly, the QosPolicies set on the DataWriter side must be compatible with corresponding policies set on the DataReader side.

For example, the RELIABILITY policy is set by the DataWriter to state whether it is configured to send data reliably to DataReaders. Because it takes additional resources to send data reliably, some DataWriters may only support a

To address this issue, and yet keep the publications and subscriptions as decoupled as possible, DCPS provides a way to detect and notify when QosPolicies set by DataWriters and DataReaders are incompatible. DCPS employs a pattern known as RxO (Requested versus Offered). The DataReader sets a “requested” value for a particular QosPolicy. The DataWriter sets an “offered” value for that QosPolicy. When Connext matches a DataReader to a DataWriter, QosPolicies are checked to make sure that all requested values can be supported by the offered values.

Application Discovery

Note that not all QosPolicies are constrained by the RxO pattern. For example, it does not make sense to compare policies that affect only the DataWriter but not the DataReader or vice versa.

If the DataWriter can not satisfy the requested QosPolicies of a DataReader, Connext will not con- nect the two entities and will notify the applications on each side of the incompatibility if so con- figured.

For example, a DataReader sets its DEADLINE QoS to 4

In one application, the DataWriter sets its DEADLINE QoS to 2

In another application, the DataWriter sets its DEADLINE QoS to 5 seconds. It only commits to sending data at 5 second intervals. This will not satisfy the request of the DataReader. Connext will flag this incompatibility by calling

For a summary of the QosPolicies supported by Connext, see QosPolicies (Section 4.2).

2.6Application Discovery

The DCPS model provides anonymous, transparent,

So how is this all done? Ultimately, in each application for each publication, Connext must keep a list of applications that have subscribed to the same Topic, nodes on which they are located, and some additional QoS parameters that control how the data is sent. Also, Connext must keep a list of applications and publications for each of the Topics to which the application has subscribed.

This propagation of this information (the existence of publications and subscriptions and associ- ated QoS) between applications by Connext is known as the discovery process. While the DDS (DCPS) standard does not specify how discovery occurs, Connext uses a standard protocol RTPS for both discovery and formatting

When a DomainParticipant is created, Connext sends out packets on the network to announce its existence. When an application finds out that another application belongs to the same domain, then it will exchange information about its existing publications and subscriptions and associ- ated QoS with the other application. As new DataWriters and DataReaders are created, this infor- mation is sent to known applications.

The Discovery process is entirely configurable by the user and is discussed extensively in Chapter 14: Discovery.

Part 2: Core Concepts

This section includes the following chapters:

❏Chapter 3: Data Types and Data Samples

Chapter 3 Data Types and Data Samples

How data is stored or laid out in memory can vary from language to language, compiler to com- piler, operating system to operating system, and processor to processor. This combination of lan- guage/compiler/operating system/processor is called a platform. Any modern middleware must be able to take data from one specific platform (say C/gcc.3.2.2/Solaris/Sparc) and trans- parently deliver it to another (for example, Java/JDK 1.6/Windows XP/Pentium). This process is commonly called serialization/deserialization, or marshalling/demarshalling.

Messaging products have typically taken one of two approaches to this problem:

1.Do nothing. Messages consist only of opaque streams of bytes. The JMS BytesMessage is an example of this approach.

2.Send everything, every time.

The “do nothing” approach is lightweight on its surface but forces you, the user of the middle- ware API, to consider all data encoding, alignment, and padding issues. The “send everything” alternative results in large amounts of redundant information being sent with every packet, impacting performance.

Connext takes an intermediate approach. Just as objects in your application program belong to some data type, data samples sent on the same Connext topic share a data type. This type defines the fields that exist in the data samples and what their constituent types are. The middleware stores and propagates this

To publish and/or subscribe to data with Connext, you will carry out the following steps:

1.Select a type to describe your data.

You have a number of choices. You can choose one of these options, or you can mix and match them.

•Use a

This option may be sufficient if your data typing needs are very simple. If your data is highly structured, or you need to be able to examine fields within that data for filter- ing or other purposes, this option may not be appropriate. The

•Use the RTI code generator, rtiddsgen, to define a type at

Code generation offers two strong benefits not available with dynamic type defini- tion: (1) it allows you to share type definitions across programming languages, and (2) because the structure of the type is known at compile time, it provides rigorous static type safety.

The code generator accepts input in a number of formats to make it easy to integrate Connext with your development processes and IT infrastructure:

•OMG IDL. This format is a standard component of both the DDS and CORBA specifications. It describes data types with a

•XML schema (XSD), either independent or embedded in a WSDL file. XSD should be the format of choice for those using Connext alongside or connected to a web- services infrastructure. This format is described in Creating User Data Types with XML Schemas (XSD) (Section 3.5).

•XML in a

•Define a type programmatically at run time.

This method may be appropriate for applications with dynamic data description needs: applications for which types change frequently or cannot be known ahead of time. It is described in Defining New Types (Section 3.8.2).

2.Register your type with a logical name.

If you've chosen to use a

This step is described in the Defining New Types (Section 3.8.2).

3.Create a Topic using the type name you previously registered.

If you've chosen to use a

Creating and working with Topics is discussed in Chapter 5: Topics.

4.Create one or more DataWriters to publish your data and one or more DataReaders to sub- scribe to it.

The concrete types of these objects depend on the concrete data type you've selected, in order to provide you with a measure of type safety.

Creating and working with DataWriters and DataReaders are described in Chapter 6: Sending Data and Chapter 7: Receiving Data, respectively.

Whether publishing or subscribing to data, you will need to know how to create and delete data samples and how to get and set their fields. These tasks are described in Working with Data Samples (Section 3.9).

This chapter describes:

❏Introduction to the Type System (Section 3.1 on Page

❏

❏Creating User Data Types with IDL (Section 3.3 on Page

❏Creating User Data Types with Extensible Markup Language (XML) (Section 3.4 on Page

Introduction to the Type System

❏Creating User Data Types with XML Schemas (XSD) (Section 3.5 on Page

❏Using rtiddsgen (Section 3.6 on Page

❏Using Generated Types without Connext (Standalone) (Section 3.7 on Page

❏Interacting Dynamically with User Data Types (Section 3.8 on Page

❏Working with Data Samples (Section 3.9 on Page

3.1Introduction to the Type System

A user data type is any custom type that your application defines for use with Connext. It may be a structure, a union, a value type, an enumeration, or a typedef (or language equivalents).

Your application can have any number of user data types. They can be composed of any of the primitive data types listed below or of other user data types.

Only structures, unions, and value types may be read and written directly by Connext; enums, typedefs, and primitive types must be contained within a structure, union, or value type. In order for a DataReader and DataWriter to communicate with each other, the data types associated with their respective Topic definitions must be identical.

❏octet, char, wchar

❏short, unsigned short

❏long, unsigned long

❏long long, unsigned long long

❏float

❏double, long double

❏boolean

❏enum (with or without explicit values)

❏bounded and unbounded string and wstring

The following

❏module (also called a package or namespace)

❏pointer

❏array of primitive or user type elements

❏bounded/unbounded sequence of

❏typedef

❏bitfield2

❏union

❏struct

❏value type, a complex type that supports inheritance and other

1.Sequences of sequences are not supported directly. To work around this constraint, typedef the inner sequence and form a sequence of that new type.

2.Data types containing bitfield members are not supported by DynamicData.

Introduction to the Type System

To use a data type with Connext, you must define that type in a way the middleware under- stands and then register the type with the middleware. These steps allow Connext to serialize, deserialize, and otherwise operate on specific types. They will be described in detail in the fol- lowing sections.

3.1.1Sequences

A sequence contains an ordered collection of elements that are all of the same type. The opera- tions supported in the sequence are documented in the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported programming languages (select Modules, DDS API Refer- ence, Infrastructure Module, Sequence Support).

Java sequences implement the java.util.List interface from the standard Collections framework.

C++ users will find sequences conceptually similar to the deque class in the Standard Template Library (STL).

Elements in a sequence are accessed with their index, just like elements in an array. Indices start from zero. Unlike arrays, however, sequences can grow in size. A sequence has two sizes associ- ated with it: a physical size (the "maximum") and a logical size (the "length"). The physical size indicates how many elements are currently allocated by the sequence to hold; the logical size indicates how many valid elements the sequence actually holds. The length can vary from zero up to the maximum. Elements cannot be accessed at indices beyond the current length.

A sequence may be declared as bounded or unbounded. A sequence's "bound" is the maximum number of elements tha tthe sequence can contain at any one time. The bound is very important because it allows Connext to preallocate buffers to hold serialized and deserialized samples of your types; these buffers are used when communicating with other nodes in your distributed system. If a sequence had no bound, Connext would not know how large to allocate its buffers and would therefore have to allocate them on the fly as individual samples were read and writ-

3.1.2Strings and Wide Strings

Connext supports both strings consisting of

Like sequences, strings may be bounded or unbounded. A string's "bound" is its maximum length (not counting the trailing NULL character in C and C++).

3.1.3Introduction to TypeCode

Type

enum TCKind { TK_NULL, TK_SHORT, TK_LONG, TK_USHORT, TK_ULONG,

TK_FLOAT,

TK_DOUBLE,

TK_BOOLEAN, TK_CHAR, TK_OCTET, TK_STRUCT, TK_UNION, TK_ENUM, TK_STRING, TK_SEQUENCE, TK_ARRAY, TK_ALIAS, TK_LONGLONG, TK_ULONGLONG, TK_LONGDOUBLE, TK_WCHAR, TK_WSTRING, TK_VALUE, TK_SPARSE

}

Type codes unambiguously match type representations and provide a more reliable test than comparing the string type names.

The TypeCode class, modeled after the corresponding CORBA API, provides access to type- code information. For details on the available operations for the TypeCode class, see the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported programming languages (select Modules, DDS API Reference, Topic Module, Type Code Support).

3.1.3.1Sending TypeCodes on the Network

In addition to being used locally, serialized type codes are typically published automatically during discovery as part of the

Note: Type codes are not cached by Connext upon receipt and are therefore not available from the

DataReader's get_matched_publication_data() operation.

If your data type has an especially complex type code, you may need to increase the value of the type_code_max_serialized_length field in the DomainParticipant's

DOMAIN_PARTICIPANT_RESOURCE_LIMITS QosPolicy (DDS Extension) (Section 8.5.4). Or, to prevent the propagation of type codes altogether, you can set this value to zero (0). Be aware that some features of monitoring tools, as well as some features of the middleware itself (such as ContentFilteredTopics) will not work correctly if you disable TypeCode propagation.

3.2

Connext provides a set of standard types that are built into the middleware. These types can be used immediately; they do not require writing IDL, invoking the rtiddsgen utility (see Section 3.6), or using the dynamic type API (see Section 3.2.8).

The supported

The

❏Registering

❏Creating Topics for

❏Creating ContentFilteredTopics for

❏String

❏KeyedString

❏Octets

❏KeyedOctets

❏Type Codes for

3.2.1Registering

By default, the

3.2.2Creating Topics for

To create a topic for a

Note: In the following examples, you will see the sentinel "<BuiltinType>."

For C and C++: <BuiltinType> = String, KeyedString, Octets or KeyedOctets For Java and .NET1: <BuiltinType> = String, KeyedString, Bytes or KeyedBytes

C API:

const char* DDS_<BuiltinType>TypeSupport_get_type_name();

C++ API with namespace:

const char* DDS::<BuiltinType>TypeSupport::get_type_name();

C++ API without namespace:

const char* DDS<BuiltinType>TypeSupport::get_type_name();

C++/CLI API:

System::String^ DDS:<BuiltinType>TypeSupport::get_type_name();

C# API:

System.String DDS.<BuiltinType>TypeSupport.get_type_name();

1. RTI Connext .NET language binding is currently supported for C# and C++/CLI.

Java API:

String com.rti.dds.type.builtin.<BuiltinType>TypeSupport.get_type_name();

3.2.2.1Topic Creation Examples

For simplicity, error handling is not shown in the following examples.

C Example:

DDS_Topic * topic = NULL;

/* Create a builtin type Topic */

topic = DDS_DomainParticipant_create_topic( participant, "StringTopic",

DDS_StringTypeSupport_get_type_name(), &DDS_TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT, NULL, DDS_STATUS_MASK_NONE);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a String builtin type Topic */ Topic * topic =

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport::get_type_name(),

DDS_TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT, NULL, DDS_STATUS_MASK_NONE);

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a builtin type Topic */

Topic^ topic =

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport::get_type_name(), DomainParticipant::TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

nullptr, StatusMask::STATUS_MASK_NONE);

C# Example:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a builtin type Topic */

Topic topic = participant.create_topic(

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport.get_type_name(), DomainParticipant.TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

null, StatusMask.STATUS_MASK_NONE);

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*;

...

/* Create a builtin type Topic */

Topic topic = participant.create_topic(

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport.get_type_name(), DomainParticipant.TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

null, StatusKind.STATUS_MASK_NONE);

3.2.3Creating ContentFilteredTopics for

To create a ContentFilteredTopic for a

The field names used in the filter expressions for the

3.2.3.1ContentFilteredTopic Creation Examples

For simplicity, error handling is not shown in the following examples.

C Example:

DDS_Topic * topic = NULL;

DDS_ContentFilteredTopic * contentFilteredTopic = NULL; struct DDS_StringSeq parameters = DDS_SEQUENCE_INITIALIZER;

/* Create a string ContentFilteredTopic */ topic = DDS_DomainParticipant_create_topic(

participant, "StringTopic", DDS_StringTypeSupport_get_type_name(), &DDS_TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,NULL, DDS_STATUS_MASK_NONE);

contentFilteredTopic = DDS_DomainParticipant_create_contentfilteredtopic( participant, "StringContentFilteredTopic",

topic, "value = 'Hello World!'", ¶meters);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a String ContentFilteredTopic */ Topic * topic =

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport::get_type_name(), TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT, NULL, STATUS_MASK_NONE);

StringSeq parameters;

ContentFilteredTopic * contentFilteredTopic =

"StringContentFilteredTopic", topic, "value = 'Hello World!'", parameters);

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a String ContentFilteredTopic */ Topic^ topic =

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport::get_type_name(), DomainParticipant::TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

nullptr, StatusMask::STATUS_MASK_NONE);

StringSeq^ parameters = gcnew StringSeq();

ContentFilteredTopic^ contentFilteredTopic =

"StringContentFilteredTopic", topic, "value = 'Hello World!'", parameters);

C# Example:

using namespace DDS;

...

/* Create a String ContentFilteredTopic */ Topic topic = participant.create_topic(

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport.get_type_name(), DomainParticipant.TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

null, StatusMask.STATUS_MASK_NONE);

StringSeq parameters = new StringSeq();

ContentFilteredTopic contentFilteredTopic = participant.create_contentfilteredtopic(

"StringContentFilteredTopic", topic, "value = 'Hello World!'", parameters);

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*;

...

/* Create a String ContentFilteredTopic */ Topic topic = participant.create_topic(

"StringTopic", StringTypeSupport.get_type_name(), DomainParticipant.TOPIC_QOS_DEFAULT,

null, StatusKind.STATUS_MASK_NONE);

StringSeq parameters = new StringSeq();

ContentFilteredTopic contentFilteredTopic = participant.create_contentfilteredtopic(

"StringContentFilteredTopic", topic, "value = 'Hello World!'", parameters);

3.2.4String

The String

3.2.4.1Creating and Deleting Strings

In C and C++, Connext provides a set of operations to create (DDS::String_alloc()), destroy (DDS::String_free()), and clone strings (DDS::String_dup()). Select Modules, DDS API Refer- ence, Infrastructure Module, String support in the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported programming languages.

1. RTI Connext .NET language binding is currently supported for C# and C++/CLI.

Memory Considerations in Copy Operations:

When the read/take operations that take a sequence of strings as a parameter are used in copy mode, Connext allocates the memory for the string elements in the sequence if they are initialized to NULL.

If the elements are not initialized to NULL, the behavior depends on the language:

•In Java and .NET, the memory associated with the elements is reallocated with every sample, because strings are immutable objects.

•In C and C++, the memory associated with the elements must be large enough to hold the received data. Insufficient memory may result in crashes.

When take_next_sample() and read_next_sample() are called in C and C++, you must make sure that the input string has enough memory to hold the received data. Insuffi- cient memory may result in crashes.

3.2.4.2String DataWriter

The string DataWriter API matches the standard DataWriter API (see Using a

The following examples show how to write simple strings with a string

C Example:

DDS_StringDataWriter * stringWriter = ... ; DDS_ReturnCode_t retCode;

char * str = NULL;

/* Write some data */

retCode = DDS_StringDataWriter_write(

stringWriter, "Hello World!", &DDS_HANDLE_NIL);

str = DDS_String_dup("Hello World!");

retCode = DDS_StringDataWriter_write(stringWriter, str, &DDS_HANDLE_NIL); DDS_String_free(str);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

StringDataWriter * stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data */

ReturnCode_t retCode =

retCode =

DDS::String_free(str);

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace System; using namespace DDS;

...

StringDataWriter^ stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data */

C# Example:

using System; using DDS;

...

StringDataWriter stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data */

stringWriter.write("Hello World!", InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL); String str = "Hello World!";

stringWriter.write(str, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.publication.*; import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*; import com.rti.dds.infrastructure.*;

...

StringDataWriter stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data */

stringWriter.write("Hello World!", InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL); String str = "Hello World!";

stringWriter.write(str, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

3.2.4.3String DataReader

The string DataReader API matches the standard DataReader API (see Using a

The following examples show how to read simple strings with a string

C Example:

struct DDS_StringSeq dataSeq = DDS_SEQUENCE_INITIALIZER; struct DDS_SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = DDS_SEQUENCE_INITIALIZER; DDS_StringDataReader * stringReader = ... ; DDS_ReturnCode_t retCode;

int i;

/* Take and print the data */

retCode = DDS_StringDataReader_take(stringReader, &dataSeq, &infoSeq, DDS_LENGTH_UNLIMITED, DDS_ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, DDS_ANY_VIEW_STATE, DDS_ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (i = 0; i < DDS_StringSeq_get_length(&data_seq); ++i) {

if (DDS_SampleInfoSeq_get_reference(&info_seq,

DDS_StringSeq_get(&data_seq, i));

}

}

/* Return loan */

retCode = DDS_StringDataReader_return_loan(stringReader, &data_seq, &info_seq);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

StringSeq dataSeq;

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq;

StringDataReader * stringReader = ... ;

/* Take a print the data */

ReturnCode_t retCode =

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if (infoSeq[i].valid_data) {

StringTypeSupport::print_data(dataSeq[i]);

}

}

/* Return loan */

retCode =

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace System; using namespace DDS;

...

StringSeq^ dataSeq = gcnew StringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq^ infoSeq = gcnew SampleInfoSeq();

StringDataReader^ stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */

ResourceLimitsQosPolicy::LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind::ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind::ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind::ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if

}

}

/* Return loan */

C# Example:

using System; using DDS;

...

StringSeq dataSeq = new StringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = new SampleInfoSeq();

StringDataReader stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */

stringReader.take(dataSeq, infoSeq, ResourceLimitsQosPolicy.LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind.ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind.ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind.ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if (infoSeq.get_at(i)).valid_data) {

StringTypeSupport.print_data(dataSeq.get_at(i));

}

}

}

}

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.infrastructure.*; import com.rti.dds.subscription.*; import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*;

...

StringSeq dataSeq = new StringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = new SampleInfoSeq();

StringDataReader stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */ stringReader.take(dataSeq, infoSeq,

ResourceLimitsQosPolicy.LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind.ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind.ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind.ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) {

if (((SampleInfo)infoSeq.get(i)).valid_data) { System.out.println((String)dataSeq.get(i));

}

}

/* Return loan */ stringReader.return_loan(dataSeq, infoSeq);

3.2.5KeyedString

The Keyed String

C/C++ Representation (without namespaces):

struct DDS_KeyedString { char * key;

char * value;

};

C++/CLI Representation:

namespace DDS {

public ref struct KeyedString: { public:

System::String^ key; System::String^ value;

...

};

};

C# Representation:

namespace DDS {

public class KeyedString { public System.String key; public System.String value;

};

};

Java Representation:

namespace DDS {

public class KeyedString { public System.String key; public System.String value;

};

};

3.2.5.1Creating and Deleting Keyed Strings

Connext provides a set of constructors/destructors to create/destroy Keyed Strings. For details, see the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported programming languages (select Modules, DDS API Reference, Topic Module,

If you want to manipulate the memory of the fields 'value' and 'key' in the KeyedString struct in C/C++, use the operations DDS::String_alloc(), DDS::String_dup(), and DDS::String_free(), as described in the API Reference HTML documentation (select Modules, DDS API Reference, Infrastructure Module, String Support).

3.2.5.2Keyed String DataWriter

The keyed string DataWriter API is extended with the following methods (in addition to the standard methods described in Using a

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::dispose( const char* key,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* instance_handle);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::dispose_w_timestamp( const char* key,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* instance_handle, const struct DDS::Time_t* source_timestamp);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::get_key_value( char * key,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle);

DDS::InstanceHandle_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::lookup_instance(

const char * key);

DDS::InstanceHandle_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::register_instance(

const char* key);

DDS::InstanceHandle_t

DDS_KeyedStringDataWriter::register_instance_w_timestamp(

const char * key,

const struct DDS_Time_t* source_timestamp);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::unregister_instance( const char * key,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::unregister_instance_w_timestamp(

const char* key,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle,

const struct DDS::Time_t* source_timestamp);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::write ( const char * key,

const char * str,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataWriter::write_w_timestamp( const char * key,

const char * str,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle,

const struct DDS::Time_t* source_timestamp);

These operations are introduced to provide maximum flexibility in the format of the input parameters for the write and instance management operations. For additional information and a complete description of the operations, see the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported programming languages.

The following examples show how to write keyed strings using a keyed string

C Example:

DDS_KeyedStringDataWriter * stringWriter = ... ; DDS_ReturnCode_t retCode;

struct DDS_KeyedString * keyedStr = NULL; char * str = NULL;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString structure */ keyedStr = DDS_KeyedString_new(255, 255);

retCode = DDS_KeyedStringDataWriter_write_string_w_key( stringWriter, keyedStr, &DDS_HANDLE_NIL);

DDS_KeyedString_delete(keyedStr);

/* Write some data using individual strings */

retCode = DDS_KeyedStringDataWriter_write_string_w_key( stringWriter, "Key 1",

"Value 1", &DDS_HANDLE_NIL);

str = DDS_String_dup("Value 2");

retCode = DDS_KeyedStringDataWriter_write_string_w_key( stringWriter, "Key 1", str, &DDS_HANDLE_NIL);

DDS_String_free(str);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

KeyedStringDataWriter * stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString */ KeyedString * keyedStr = new KeyedString(255, 255);

ReturnCode_t retCode =

delete keyedStr;

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

KeyedStringDataWriter * stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString */ KeyedString * keyedStr = new KeyedString(255, 255);

ReturnCode_t retCode =

delete keyedStr;

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace System; using namespace DDS;

...

KeyedStringDataWriter^ stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString */ KeyedString^ keyedStr = gcnew KeyedString();

/* Write some data using individual strings */

String^ str = "Value 2";

C# Example

using System; using DDS;

...

KeyedStringDataWriter stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString */ KeyedString keyedStr = new KeyedString(); keyedStr.key = "Key 1";

keyedStr.value = "Value 1";

stringWriter.write(keyedStr, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

/* Write some data using individual strings */ stringWriter.write("Key 1", "Value 1", InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

String str = "Value 2";

stringWriter.write("Key 1", str, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

Java Example :

import com.rti.dds.publication.*; import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*; import com.rti.dds.infrastructure.*;

...

KeyedStringDataWriter stringWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the KeyedString */ KeyedString keyedStr = new KeyedString(); keyedStr.key = "Key 1";

keyedStr.value = "Value 1";

stringWriter.write(keyedStr, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

/* Write some data using individual strings */ stringWriter.write("Key 1", "Value 1", InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

String str = "Value 2";

stringWriter.write("Key 1", str, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

3.2.5.3Keyed String DataReader

The KeyedString DataReader API is extended with the following operations (in addition to the standard methods described in Using a

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::KeyedStringDataReader::get_key_value(

char * key, const DDS::InstanceHandle_t* handle);

DDS::InstanceHandle_t DDS::KeyedStringDataReader::lookup_instance(

const char * key);

For additional information and a complete description of these operations in all supported lan- guages, see the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported pro- gramming languages.

Memory considerations in copy operations:

For read/take operations with copy semantics, such as read_next_sample() and take_next_sample(), Connext allocates memory for the fields 'value' and 'key' if they are initialized to NULL.

If the fields are not initialized to NULL, the behavior depends on the language:

•In Java and .NET, the memory associated to the fields 'value' and 'key' will be reallo- cated with every sample.

•In C and C++, the memory associated with the fields 'value' and 'key' must be large enough to hold the received data. Insufficient memory may result in crashes.

The following examples show how to read keyed strings with a keyed string

C Example:

struct DDS_KeyedStringSeq dataSeq = DDS_SEQUENCE_INITIALIZER; struct DDS_SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = DDS_SEQUENCE_INITIALIZER; DDS_KeyedKeyedStringDataReader * stringReader = ... ; DDS_ReturnCode_t retCode;

int i;

/* Take and print the data */

retCode = DDS_KeyedStringDataReader_take(stringReader, &dataSeq, &infoSeq, DDS_LENGTH_UNLIMITED, DDS_ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, DDS_ANY_VIEW_STATE, DDS_ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (i = 0; i < DDS_KeyedStringSeq_get_length(&data_seq); ++i) {

if (DDS_SampleInfoSeq_get_reference(&info_seq,

DDS_KeyedStringSeq_get_reference(&data_seq, i));

}

}

/* Return loan */

retCode = DDS_KeyedStringDataReader_return_loan(

stringReader, &data_seq, &info_seq);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

KeyedStringSeq dataSeq;

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq;

KeyedStringDataReader * stringReader = ... ;

/* Take a print the data */

ReturnCode_t retCode =

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if (infoSeq[i].valid_data) {

KeyedStringTypeSupport::print_data(&dataSeq[i]);

}

}

/* Return loan */

retCode =

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace System; using namespace DDS;

...

KeyedStringSeq^ dataSeq = gcnew KeyedStringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq^ infoSeq = gcnew SampleInfoSeq();

KeyedStringDataReader^ stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */

ResourceLimitsQosPolicy::LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind::ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind::ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind::ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if

}

}

/* Return loan */

C# Example:

using System; using DDS;

...

KeyedStringSeq dataSeq = new KeyedStringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = new SampleInfoSeq();

KeyedStringDataReader stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */ stringReader.take(dataSeq, infoSeq,

ResourceLimitsQosPolicy.LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind.ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind.ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind.ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) { if (infoSeq.get_at(i)).valid_data) {

KeyedStringTypeSupport.print_data(dataSeq.get_at(i));

}

}

/* Return loan */ stringReader.return_loan(dataSeq, infoSeq);

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.infrastructure.*; import com.rti.dds.subscription.*; import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*;

...

KeyedStringSeq dataSeq = new KeyedStringSeq();

SampleInfoSeq infoSeq = new SampleInfoSeq();

KeyedStringDataReader stringReader = ... ;

/* Take and print the data */ stringReader.take(dataSeq, infoSeq,

ResourceLimitsQosPolicy.LENGTH_UNLIMITED, SampleStateKind.ANY_SAMPLE_STATE, ViewStateKind.ANY_VIEW_STATE, InstanceStateKind.ANY_INSTANCE_STATE);

for (int i = 0; i < data_seq.length(); ++i) {

if (((SampleInfo)infoSeq.get(i)).valid_data) { System.out.println((

(KeyedString)dataSeq.get(i)).toString());

}

}

/* Return loan */ stringReader.return_loan(dataSeq, infoSeq);

3.2.6Octets

The octets

C/C++ Representation (without Namespaces):

struct DDS_Octets { int length;

unsigned char * value;

};

C++/CLI Representation:

namespace DDS {

public ref struct Bytes: { public:

System::Int32 length; System::Int32 offset; array<System::Byte>^ value;

...

};

};

C# Representation:

namespace DDS {

public class Bytes {

public System.Int32 length; public System.Int32 offset; public System.Byte[] value;

...

};

};

Java Representation:

package com.rti.dds.type.builtin;

public class Bytes implements Copyable { public int length;

public int offset; public byte[] value;

...

};

3.2.6.1Creating and Deleting Octets

Connext provides a set of constructors/destructors to create and destroy Octet objects. For details, see the API Reference HTML documentation, which is available for all supported pro- gramming languages (select Modules, DDS API Reference, Topic Module,

If you want to manipulate the memory of the value field inside the Octets struct in C/C++, use the operations DDS::OctetBuffer_alloc(), DDS::OctetBuffer_dup(), and

DDS::OctetBuffer_free(), described in the API Reference HTML documentation (select Mod- ules, DDS API Reference, Infrastructure Module, Octet Buffer Support).

3.2.6.2Octets DataWriter

In addition to the standard methods (see Using a

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::OctetsDataWriter::write(

const DDS::OctetSeq & octets,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t & handle);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::OctetsDataWriter::write(

const unsigned char * octets, int length,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t& handle);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::OctetsDataWriter::write_w_timestamp( const DDS::OctetSeq & octets,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t & handle, const DDS::Time_t & source_timestamp);

DDS::ReturnCode_t DDS::OctetsDataWriter::write_w_timestamp( const unsigned char * octets, int length,

const DDS::InstanceHandle_t& handle, const DDS::Time_t& source_timestamp);

These methods are introduced to provide maximum flexibility in the format of the input param- eters for the write operations. For additional information and a complete description of these operations in all supported languages, see the API Reference HTML documentation.

The following examples show how to write an array of octets using an octets

C Example:

DDS_OctetsDataWriter * octetsWriter = ... ; DDS_ReturnCode_t retCode;

struct DDS_Octets * octets = NULL; char * octetArray = NULL;

/* Write some data using the Octets structure */ octets = DDS_Octets_new_w_size(1024);

retCode = DDS_OctetsDataWriter_write(octetsWriter, octets, &DDS_HANDLE_NIL); DDS_Octets_delete(octets);

/* Write some data using an octets array */ octetArray = (unsigned char *)malloc(1024); octetArray[0] = 46;

octetArray[1] = 47;

retCode = DDS_OctetsDataWriter_write_octets (octetsWriter, octetArray, 2, &DDS_HANDLE_NIL);

free(octetArray);

C++ Example with Namespaces:

#include "ndds/ndds_namespace_cpp.h" using namespace DDS;

...

OctetsDataWriter * octetsWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the Octets structure */ Octets * octets = new Octets(1024);

ReturnCode_t retCode =

delete octets;

/* Write |

some |

data using an octet array */ |

unsigned |

char |

* octetArray = new unsigned char[1024]; |

octetArray[0] |

= 46; |

|

octetArray[1] |

= 47; |

|

retCode =

delete []octetArray;

C++/CLI Example:

using namespace System; using namespace DDS;

...

BytesDataWriter^ octetsWriter = ...;

/* Write some data using Bytes */ Bytes^ octets = gcnew Bytes(1024);

octets.offset = 0;

/* Write some data using individual strings */ array<Byte>^ octetAray = gcnew array<Byte>(1024); octetArray[0] = 46;

octetArray[1] = 47;

C# Example:

using System; using DDS;

...

BytesDataWriter stringWriter = ...;

/* Write some data using the Bytes */ Bytes octets = new Bytes(1024); octets.value[0] = 46;

octets.value[1] = 47; octets.length = 2; octets.offset = 0;

octetWriter.write(octets, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

/* Write some data using individual strings */ byte[] octetArray = new byte[1024]; octetArray[0] = 46;

octetArray[1] = 47;

octetsWriter.write(octetArray, 0, 2, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

Java Example:

import com.rti.dds.publication.*; import com.rti.dds.type.builtin.*; import com.rti.dds.infrastructure.*;

...

BytesDataWriter octetsWriter = ... ;

/* Write some data using the Bytes class*/ Bytes octets = new Bytes(1024); octets.length = 2;

octets.offset = 0; octets.value[0] = 46; octets.value[1] = 47;

octetsWriter.write(octets, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

/* Write some data using a byte array */ byte[] octetArray = new byte[1024]; octetArray[0] = 46;

octetArray[1] = 47;

octetsWriter.write(octetArray, 0, 2, InstanceHandle_t.HANDLE_NIL);

3.2.6.3Octets DataReader

The octets DataReader API matches the standard DataReader API (see Using a

Memory considerations in copy operations: